For some Angelenos, the 20th anniversary of the L.A. Riots brings to mind another traumatic event from an even earlier time: The Watts Riots of 1965.

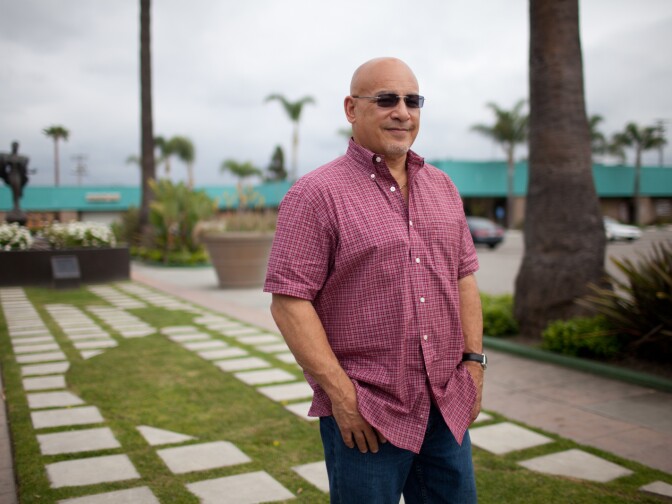

“Sweet Alice" Harris - as people call her - is 76 years-old, and has lived in Watts much of her life. I visited Harris at "Parents of Watts," the nonprofit she’s been running for several decades. Harris has a different take on the L.A. Riots.

“The reason [the 1992 LA Riots] didn’t get big [as the Watts Riots] is we stopped it," Harris says. "I was here and I know.”

Some people call the events the Watts “civil unrest.” The violence erupted in August of 1965 after a tense confrontation between a white California Highway Patrol Officer and a 21 year-old black man suspected of driving while intoxicated. Officers used force to subdue the driver, while a gathering crowd grew bigger, and angrier.

For five days, thousands of people burned buildings and looted businesses.

“People was already mad, already upset," says Harris.

She says the community felt ignored and that problems with high unemployment, racism and police brutality were not being addressed.

KPCC Washington correspondent Kitty Felde was a child living in nearby Compton during that summer of ’65. Decades later, she covered the L.A. Riots.

“Well, both of them were sparked by police incidents," Felde recalls. "Both of them, sparked by economic inequities. And people basically saying ‘I’ve had enough.’"

"I guess you could portray ’65 as a real black and white event in many ways," Felde adds. "I mean literally, that’s how it showed up in the newspaper and that’s how it was perceived. ’92 was a little more, shall we say, diverse.”

Susan Jefferson was seven months pregnant with her first child during the Watts Riots. Members of her family worked and lived there. Jefferson believes the media painted a negative portrait of the community at the time.

“It was a small minority of people that caused that riot, compared to the amount of people that lived there and went to work everyday and raised their families and that really bothered me.”

“Big differences between the two riots - one being of a nationalist orientation, a revolt but with a black power symbol behind it," says Tim Watkins, who runs the Watts Labor Community Action Committee (WLCAC), a group founded by his father, Ted Watkins.

The younger Watkins says his dad was motivated by increasing tensions between African Americans and Latinos in the neighborhood.

“Black and brown people that are suffering from poor education, lack of housing and unemployment, poor health, all the same stuff that we have going on here today, need to come together without any others at the table."

“Sweet Alice" Harris says she recognized that need. She worked with a Latino community leader she remembers as ‘Ms. McDrummond’ to rally L.A. Mayor Tom Bradley to bring more jobs to Watts.

“Mayor Bradley gave us 30 summer jobs," Harris remembers. "Ms. McDrummond and I got together and said ‘whatever we do for blacks, what we do for the blacks, we gonna do for the browns. It ain’t gonna be no different.'”

Harris told me that effort prevented another outbreak of violence that would have erupted much sooner than 1992.

As I leave her “Parents of Watts” establishment, I notice dozens of photographs with just about every well known politician you can think of.

One photo makes her especially proud. She’s standing arm in arm with Ms. McDrummond, on Lou Dillon Avenue where they both worked to rebuild this South L-A community they loved so much.

That pride, says Harris, has never changed.