This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

Sacheen Littlefeather Dared To Be Heard And That Mattered To Native Americans Like Me

I was only 6 years old when Sacheen Littlefeather took the stage at the Oscars, accepting the best actor trophy on behalf of Marlon Brando and issuing a simple plea for fairer treatment of Native Americans, both on screen and off.

Native Americans just like me.

But I can still remember my grandparents — my dad’s parents, my dad’s white, Irish American parents — sneering at the TV during the media uproar that followed: “Who does she think she is?”

Littlefeather quite simply walked into a buzzsaw of racism, sexism and Hollywood elitism. She dared to hold a mirror up to an America that preferred to think of Native Americans as a quaint memory of years gone by. Certainly not a group of people with any clout, much less the standing to demand justice of the masses.

The backlash was immense, and immediate. She was accused of being a stripper, people said she wasn’t “really” Native American, that she was actually Mexican. (Littlefeather said her mother was white, her father from the Apache and Yaqui tribes from Arizona.) That the buckskin dress she wore the night of the Oscars was a cheap prop, instead of a prized family heirloom. Although Littlefeather said she and Brando bonded over activism, and were never more than friends, many dismissed her as Brando’s side piece.

I might only have been 6, going on 7, but I knew enough to know that Littlefeather “had stepped out of line” in a society that didn’t want to hear her message.

That was the biggest insult that could be delivered in my family, variations along the theme of “Know your place” and “Don’t you dare step out of line, or else…”

My mother grew up in North Carolina, a sharecropper’s daughter. Her parents — both Lumbee Indians — were so poor they didn’t get indoor plumbing until I was a teenager. During our Easter and summer visits down South, I remember thinking fetching water from the well was fun, although using the outhouse was not.

My mother was no fan of outhouses either, or the grueling work of a farm hand, plowing by mule, plucking cotton and harvesting tobacco by hand, and missing her senior school dance because there were chores to be done. As soon as she was old enough, she fled north, to New Jersey. And a proverbial shotgun wedding to an Irish American white man, my father, came soon after.

You’re marrying a white man? That’s your family now.

It was a marriage that would tear both families apart, coming one year before the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision overturning a Virginia ban against interracial marriage.

“You’re marrying a white man?” My grandfather told her she no longer had a place in his home. “That’s your family now,” he said.

My father’s parents were equally aggrieved, and cut off contact. They couldn’t quite comprehend the idea of my mother being Native American, and they kept calling her Black. Only they used a different word. My father said that when he called my grandmother to inform her of my birth — hoping it would freeze the thaw between them — she asked of her new granddaughter: “What color is she?”

My dad hung up, and they didn’t speak again for nearly a year.

But then hard times hit close to home. My father was part of the gig economy before that was even a term. His jobs doing waterfront construction work and driving trucks relied upon good weather.

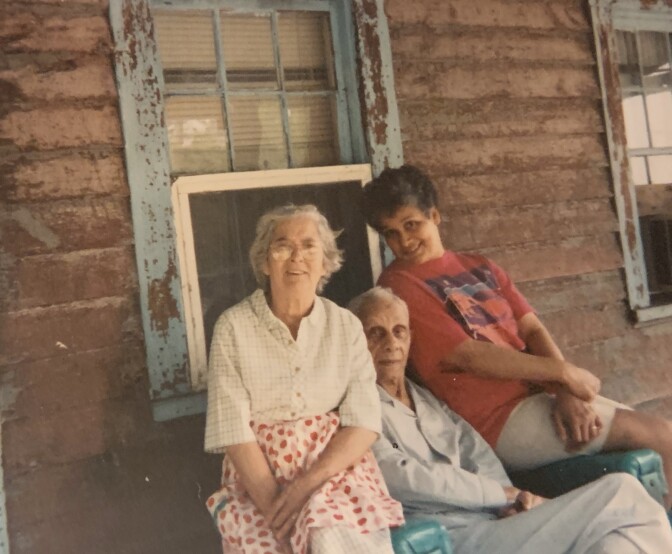

During one particularly bad year, he had to pick up the phone and call my grandmother. I was 4 years old when we moved in with my father’s mom and dad. While my paternal grandparents were usually loving and kind, they did their best to make my brother and I — and especially my mother — cut ties with my mother’s family.

“Why do you want to go there?” they’d press my mother when she wanted to visit her family in the South, their distaste clearly evident. “You like it better here, right?” they’d nudge me and my brother.

With us living under their roof, my grandparents felt free to dole out reprimands to all three of us alike with a hissed “Just who do you think you are…” whether it was for not getting better grades, for playing too loudly or for my mother’s bouffant hairdo, which they felt was too extravagant and required too much maintenance. My mother has worn it short ever since.

Know your place. Don’t step out of line. Don’t draw attention to yourself. You don’t think you’re better than everyone else, do you?

Because the answer was, of course not.

I didn't think much about Littlefeather again until earlier this year, when I had the opportunity to revisit her speech and her life when I was asked to write about her episode of LAist Studios’ The Academy Podcast. I was struck by how many people tried to undermine Littlefeather by, essentially, gaslighting her: She was half-white, so she wasn't a "real" Indian anyway, these weren't real issues.

Can you think of any other group of people told they weren't "real" fill-in-the-blanks because one parent was white? Yet it happens to Native Americans all the time.

Full breed, half breed, in this hierarchy, white was better than Native American. So just pipe down. If you must be seen, at least not be heard.

Well, Littlefeather dared to be heard. And spent the rest of her life paying for it. “Red listed,” as she put it. All but formally banned from Hollywood.

"I'm not afraid to die," she told us, in one of the last interviews before her death. "Because my spirit is going to go on.”

And her death this week wasn’t exactly shocking. She’d been in poor health and seemed frail when she was honored just weeks ago by the Academy of Motion Pictures and Sciences. When she was given a blanket as a gift, she quipped: “How did you know I was cold?”

In an outtake from the interview earlier this year that didn’t make it into the podcast, she explained how she saw the end of life as a Native American.

“And what we do is we start to give everything we have away before we go,” she said, “so that we have nothing to cling to here. Not even our bodies. We don't take that with us. Our spirit is free.”

Her death coming so closely on the heels of the Academy’s formal apology? After she finally got the respect that she was denied, and that everyone deserves?

It feels like justice. As if perhaps she was able to let go, perhaps willed herself to let go, after completing the job she’d set out to do nearly 50 years ago.